Hi, I’m Greig — welcome! Here you’ll find sharp writing, creative ideas, and standout resources for teaching, thinking, making, and dreaming in the middle and high school ELA and Humanities classroom (Grades 6–12).

22.1.11

The 4 Train On Sunday

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

16.9.10

Childhood Sexual Abuse and the Binary of Body/Mind in Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway

|

| Virginia Woolf, Childhood Portrait |

There rushes at once through my flesh tingling fire,

My eyes are deprived of all power of vision,

My ears hear nothing but sounds of winds roaring,

And all is blackness.

-- Sappho

Thick of waist, large of limb, and, save for her hair, fashionable in the tight modern way, she never looked like Sappho, or one of the beautiful young men whose photographs adorned the weekly papers. She looked what she was ...

-- Virginia Woolf in Between the Acts

But often now this body she wore (she stopped to look at a Dutch picture), this body, with all its capacities, seemed nothing -- nothing at all.

-- Virginia Woolf in Mrs. Dalloway

|

| Virginia Woolf and Violet Dickinson (Top); Virginia Woolf |

Louise DeSalvo’s book on childhood sexual abuse and Virginia Woolf describes how as a young girl, Virginia Stephen was abused by her half-brothers, George and Gerald Duckworth (children from her mother’s first marriage)—the extent of which we do not know much. Although much contested and controversial, we do know that something happened to Woolf that deeply marked her as an adolescent, a young woman, and throughout her adult years, influencing her subsequent body of writings, essays, and novels, especially.[1] While not the whole story, the account of abuse by George and Gerald Duckworth is a reliable source we have concerning Virginia Woolf as a sexually abused child and adolescent. George and Gerald, as recounted in biographical sketches 22 Hyde Park Gate and A Sketch of the Past, abused Virginia until she was in her twenties.[2] In A Sketch of the Past, she writes that as a child (she was about five years old), Gerald Duckworth, the youngest of the Duckworth boys, lifted her up on a high ledge when she was sick with flu and explored her body, even her private parts (Moments of Being, 69). Woolf would write, reflecting on this incident, how this tarnished her view of her own body and her distaste for mirrors. In 22 Hyde Park Gate, Woolf disturbingly describes (she was a young woman at this time) how George Duckworth crept into her room one night after an evening dinner party and crawled into bed with her; the disturbing part of her retelling is not the actual incident itself, but Woolf’s coy attitude about it, because she knows the scandal it would bring if the society ladies knew she was her half-brother’s lover (Moments of Being)![3]

There is a definite shift in mood from Hyde Park Gate, written at the height of Woolf’s career, and A Sketch of the Past written at the end of her life. The former is separated from the events—as if they were another story, not really happening to her, Virginia—her body being violated—but the latter piece is in touch with the incest that happened, bitterly cognizant of how it disconnected her from her own body, her own freedom to feel and live spontaneously. This was due in part to the oppressive patriarchy she felt under the ruling monarchy of her father, Leslie Stephen. The most explicit image of Woolf and the effects of the abused body can be seen in contrasting images of her. Consider the more beautiful images of Woolf one sees in biographies or in film. Nicole Kidman’s Woolf in The Hours, even with the prosthetic nose, is plainly beautiful, but when you notice one photograph (figure 1, top) from 1902 of Woolf in biographies, it seems her soul has been dug out of her body; she looks hollow and alone and profoundly insecure, clinging to Violet Dickinson for protection, radically contrasted to this photograph from the same year (figure 1, bottom), a profile shot that is highly publicized in books, websites, and magazines about Woolf.[4]

Of course, it is dangerous and misguided to pinpoint one event as the source for Woolf’s most revealing writings about abuse and the body, for one could point out that the subjugation she felt as a woman—not able to procure a degree from the University like her brothers—embittered her, as well as the role her mother and father played in her life (for better or worse)—her mother’s illness, her subsequent absences, her father’s patriarchy and then, of course, their deaths, her move to Bloomsbury, and her marriage to Leonard Woolf.

Psychologists will point out that children who suffer from sexual abuse often express their inchoate feelings and fears in art—painting and writing. Controversial even today, research on sexual abuse and children relies on the Rorschach test, the artwork of children, the TAT test, children’s own stories and other measures designed to assess whether or not a child has been sexually abused. There is no universal sorter to determine sexual abuse of a child, but most mental health professionals will agree that a child abused “speaks out about the abuse” in ways not always decipherable by language. It oozes out of them from every corner of their creative side, in their language and their very bodies. And probably, in this way, as a girl, Virginia Stephen learned to suppress her feelings and memories, possibly not feeling she had a safe space to express her feelings openly—except, save, for her art. In her writings, perhaps, she explores dimensions of her own coded body—unconsciously or consciously (it doesn’t make a difference)—in a way that was safe for her to express what was going on inside of her.[5]

We do not need to know the details of Woolf’s traumatic childhood experiences to find in her novels examples of abused, neglected children and wounded individuals. Nor do we need evidence that she was actually sexually abused. The text deconstructs itself, laying bare the unprivileged body in the mess and midst of mind. DeSalvo mentions that every one of her novels describes a child abandoned, a child ignored, a child at risk, a child abused, a child betrayed (see DeSalvo, p. 14).[6] In Woolf, there is a pervasive feeling that the very self has been invaded from all sides—the woman questioning her position in society in A Room of One’s Own or a boy bitterly confused by his father’s sharp disavowal of his wishes in To the Lighthouse or a woman’s wish to eradicate her own body for another in Mrs. Dalloway or the androgynous awareness of body that metamorphoses in Orlando. For fear of being too ambitious, this paper will only focus on one of Woolf’s works, Mrs. Dalloway—not precluding the possibility of applying this thesis to her other works as well.

The body in Woolf’s work considerably bespeaks of an abused individual, broken off, as it were, from an image of the body that is apparently whole and complete. Many abuse victims speak of being frozen at the time of their abuse, unable to release themselves (or unaware that they are caught) from their past. Their very image of the body, then, becomes frozen, stunted. If writing is symptomatic of the soul—if it gives us a glimpse into fractured humanity—then it is true that the novel, even more so, details the human person even to the point of what it means to be a body in space—perhaps a body broken in space, but a body with a mind—a soul—nonetheless.

But we must ask at this point, “so what?” So what that Virginia Woolf was sexually abused as a child. There is nothing we can do about that now. Everyone who could now speak first-hand about it is dead. “So what?” that she expresses her abuse in her life-work and novels—she had to find some way to exorcise these demons, so it is only natural that she would use her work to do so. The question we must ask is, how is this important for Woolf studies? What contribution—if any—did Woolf make for literature, writing about Mrs. Dalloway and Septimus Smith’s body (for instance) as an abused individual? How did she reconceptualize the often-discussed binary of body/mind so prevalent in Western thought into an often overlooked emphasis on body abused and fractured, peeking out from within a text privileged by mind?

When one thinks of Woolf, one often thinks of the Modernist project at the beginning of the twentieth century that articulated consciousness. We think of Joyce and Mansfield, literature between the two great wars. We think of stream of consciousness and wordplay so often talked about in conversations about Woolf and Joyce and others like them. We tend to think of them as lost in their heads, not really concerned with the trappings of the body but more concerned with words and the colorful display of language.

But we must take a second look to see how the text writes the body, as brought forth by the pain and loss Woolf’s characters feel (and by Woolf’s own pain and loss, as well), although it does, in fact, seem with Woolf (and the other Moderns) that she emphasizes mind over body to a degree that sometimes nears solipsism. “How am I ever going to get out of the mind of Mrs. Dalloway?” you may wonder. It may take a violent explosion. And it does. When teaching Woolf, it is often pointed out to students that reading Woolf is hard because you have to follow the thought patterns of various other minds.[7] All too often, Woolf is interpreted as being lost in the clouds—a dainty walk in London completely adrift in her own world—an interpretation used to caution students not to get lost themselves in trying to maneuver their way through the text. But we forget the violent explosions in Woolf, the often visceral, shake-you-up episodes where the body is exposed raw. The exposed, raw body, the abused body, is present in Woolf, just subtler than the trippings of mind. In Mrs. Dalloway, I argue, the characters of Septimus Smith and Clarissa Dalloway are images of abuse—sexual or physical, although the text does not explicitly reveal what kind of abuse—abuse is there—shaken and raw, speaking their voices from within the text.

In Mrs. Dalloway a violent explosion from outside on Bond Street jerks Clarissa out of her mind and into her body and by a parallel of events, Septimus Smith as well. Clarissa is choosing sweet peas for her party later that evening—her mind is in a whirl—then, like a “pistol shot” there is a violent explosion from outside (175). Septimus is walking on the other side of the street with his wife Lucrezia and when he hears the explosion there is the line: “The throb of the motor engines sounded like a pulse irregularly drumming through an entire body.” (176).

We forget the visceral side of Woolf in this scene, often thought of in popular discussions of the novel to be more concerned with how consciousness is involved—how the texts switch between Clarissa’s perception of events and Septimus’s. But what happens to the body here? When the text is deconstructed, we can see the playful interplay between mind and body at work. Clarissa, moments before the car crash, allows the soft words of Miss Pym, the florist, to wash over her like a wave to surmount a monster of hatred inside of herself—and then the violent explosion; she goes to the street, her “lips pursed with curiosity”—as if keeping the monster inside her body (Woolf 174-176). The monster is the abused, unprivileged body. Clarissa is able to “escape,” keeping the monster at bay, and then suddenly, out of nowhere, something from the outside, something external and loud violates her, shaking her consciousness to a mere image of the body.

For Septimus, at the same moment, the “world has raised its whip; where will it descend?” (176). The raised whip is the abuse. Septimus, paranoid, a veteran of the First World War, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, erroneously thinks traffic has stopped because of him. “It is I who am blocking the way, he thought” (176). For Septimus, the violent explosion from the motorcar is like the world’s whip ready to strike him dead, like the tail of Dante’s Minos coiling around the damned bodies in hell. And then again there is that line: “The throb of the motor engines sounded like a pulse irregularly drumming through an entire body.” (176). For both Septimus and Clarissa, the violence of the car crash has assaulted consciousness and manifested itself in their very own bodies; as well as the body of the text, the repressed body of coded language and abuse in Woolf. For the abused body, a sound or a touch retroactively brings the body back to the moment of abuse (very similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, as well); like an awful smell that really isn’t there but the memory of it makes it appear as if it really is; that is the stranglehold of abuse and its hold on the body.[8]

In a more subtle way, this explosion of body occurs a few scenes before the previous one in which Clarissa is window shopping on Bond Street; here again is an explosion, a rush of visceral awareness that shakes the text slightly, attempts to speak from its unprivileged position as body (170). Mind is privileged in this novel but body claws its way through the floorboards, lurking in the language and sentence structure, the otherwise words and sentences in the book we would call aporia, unsolvable instances irreconcilable with mind. Clarissa is shaken out of consciousness, out of her own head into an awareness of body when she has an intimation of her own mortality, her own transient existence—can she survive the “ebb and flow of things” (171)? She feels her body is contingent and once she dies her body will be gone forever except for the hope that her mind will live on, preserve her memories of Peter Walsh, of Richard—but body attempts to speak over mind, asserting itself in the language as aporia, the missing, abused body that seeks to be recovered (171). Death is incomprehensible to Clarissa; she is terrified to reconcile this body she wears with a final finitude. This observation of death only drives Clarissa to further insecurity, not a religious hope in a life after death.

What prompts Clarissa into an examination of her own finite, insecure body here is that she realizes that she speaks and acts only to please other people, not thinking for herself, but rather playing a part, unlike, she feels, Richard or Lady Bexborough. Clarissa realizes that “no one was ever for a second taken in” by her charms and ladylike manners; she intuits that people see beneath her class-conscious poise (171). Clarissa wants to be free, to be different—not just on the order of mind, but of the body as well—from the life she has been consigned; this is why death frightens her. Characteristic of abuse, she wishes to be someone (or something) she is not, which creates a tremor in the text, a tension between who she is, in essence, to whom we would rather be. She does not wish to have the body she wears, her own body, but rather wishes to wear another body. This is a form of despair. The text jumps from lingering in the realm of mind to actually leaping into the alterity of Lady Bexborough, whom Clarissa would rather be, a body she would rather possess. What is the cause of this radical desire to eradicate your own body? Is there a trauma that would precipitate such a claim?

Woolf herself felt that the greatest catastrophe for a woman was to be married; marriage is the great trauma. Clarissa may have been a different woman if she had not been married. This is a rational claim. Many of us often wonder what our lives would have been like if we had chosen a different path in life. For Clarissa, maybe her desire to be like Lady Bexborough or to be different and independent as Richard is an inverse reflection of the memory of the happiest moment of her life, passionately kissing Sally Seton? Though she still wears the same body, Clarissa believes she can wish body away by fantasizing being somebody else; the spasms continue to haunt her, the explosions still course through her body as when she places the brooch down on her bedroom table; Clarissa feels she can suppress this feeling, as if she can stave off the icy claws (196). Yes, it is true, Clarissa is not happy in her marriage, and possibly wished for a happier life—maybe fantasized a life with Sally Seton—but it is must be said that not only the marriage itself churns disgust about her own body. There is something else.

Still wearing the same body, she may have been a different woman but not a different body; there is something else at stake, besides marriage as the great catastrophe. Something irrational. It is not only a failed marriage that causes Clarissa to wish for Lady Bexborough’s skin of “crumpled leather and beautiful eyes” (172). This wish or desire to be another body is a form of the coded body Woolf employed in her writing, an encryption in the body of the text, abused and broken. In Clarissa’s own eyes, her body is narrow and pea-stick shaped “with a ridiculous little face, beaked like a bird’s” (172). Ironically, Clarissa’s body is the favored figure of today’s beauty magazines; the models in the slick pages of popular magazines portray the slim, skeletal body as desirable instead of the fuller, fleshed out body of a Lady Bexborough. Something about Clarissa’s culture—or her own life experience—has informed how her own body should be, adding to her anxiety to want another body just as today’s glossy magazines convince woman to lose even more weight; the slimmer the models in beauty magazines, the slimmer the body-image emblazoned on women’s brains, especially abused women who already have an insecure image of body. Even Clarissa’s internalized positive image of body is an informed construct; her observation that she holds herself well and that she has nice hands and feet, that she dresses well and so on are just as much informed by the outline traced over her own body as the wish to be a completely “other” body.[9]

When Clarissa stops to look in the window on Bond Street, she stops to look at a Dutch picture probably propped up in a display window. In one sentence: “But often now this body she wore (she stopped to look at a Dutch picture), this body, with all its capacities, seemed nothing—nothing at all.” Woolf sums up the abused body, both unhappy with body and transfixed by body—even in her loathing diatribe about the ‘body she wears” she is able to stop and see beauty in a shop window despite the fact that the beauty Clarissa notices is outside of herself. Woolf does not describe the Dutch picture in the window; the text parenthetically mentions—in passing, barely noticeable in the text if one is racing through the book—but it is there, this Dutch picture placed in contraposition to Clarissa’s own body, another extension of the fantasy to not only be someone else’s body but to attach onto an image this same irrational wish! For the abused body, for Woolf herself, spontaneous appreciation of beauty is not difficult, but made difficult by abuse—like James in To the Lighthouse, a disavowal by her father, the smothering patrimony she experienced in the Stephen household prevented her from fully expressing beauty in the open; like Clarissa, Woolf expresses beauty in parenthesis—the image of beauty for the abused is couched by a feeling of having no capacity for anything, nothing at all. While the text does not reveal the root of Clarissa Dalloway’s abuse, whether it is marriage itself, or something deeper in her past, after Bourton, when she felt free with Sally Seton, we can assume that something in Clarissa’s past marred her body, smeared her own conception of body to make her feel as if she is nothing, nothing at all. Like Woolf, traced by her half-brother’s hand, Clarissa’s body has been traced, etched upon, manipulated to the extent that Clarissa no longer feels free to be in her own body.

And Septimus is the same, unable to feel and sense beauty, despite his wife’s exclamation, “Beautiful!” (243). Septimus is not able to see beauty behind a pane of glass, etched by war to loathe his own body. “Where he had once seen mountains, where he had seen faces, where he had seen beauty, there was a screen” (296). Where he once had felt love with a fellow soldier during the war, now there is only his abused body without a friend, “macerated until only the nerve fibers were left; it was spread like a veil on a rock” (225).

This is despair Septimus and Clarissa feel, except Septimus goes one step further: his despair is not just a wish to have another body but actually to extinguish his own body; his body no longer has the capacity to sustain him any longer.[10] While Clarissa merely laments that her body is nothing, nothing at all, Septimus goes one step further into despair. Septimus Smith is an abused body; war-scarred and torn up emotionally to such an extreme extent that his friendship, his love for Evans, a fellow soldier during the war, nor the love of his wife or child can release him from the pain he feels. And when he cries out Evan’s name there is no answer, only the sound of mice squeaking and a rustled curtain, the voices of the dead (296). Throughout the novel, Septimus has discourse with the dead: with the dead Evans, with dead bodies dressed in grey; Septimus can’t stand the voices of the dead in his head, crying, “It was awful, awful!” (226). It is no wonder that Septimus is reading Dante’s Inferno, literally septic as his name implies; the Inferno, death, is his only consolation, that which helps him not to be afraid (243). This body they both wear, Clarissa and Septimus, are what they both share in common. While Clarissa, the upper-class British society woman, lives, the middle-class soldier with a wife and child dies. The poet dies so Clarissa can live. Clarissa is able to maintain her body (even though she doesn’t do the best job at it) while Septimus is unable to continue wearing this body.

“Fear no more, says the heart in the body; fear no more,” thinks Septimus (290). The pain and the abuse come to a head, despite his own self-consoling, Septimus flings himself onto “Mrs. Filmer’s area railings” (299).[11] But Septimus is not afraid. The stranglehold of abuse may have gotten the best of him, driven him to suicide, but he is not afraid of death like Clarissa. The last image we have of Clarissa is holding onto the banister at the top of the stairs, finally able to give her party. The final image of Septimus is a mangled body. Clarissa is able to stave off the monsters inside of her, for a time. Or is she? Just because Clarissa lives and Septimus dies does not exonerate Clarissa. Septimus’s death releases Lucrezia; she sighs relief when he dies. His death exonerates his pain. Clarissa has to face her problems. Clarissa still is not free. Clarissa is not yet able to say to the heart in the body, fear no more, fear no more. Yet both Clarissa and Septimus are both heroes in this story, because they speak to victims of abuse, at whatever stage in life, not in the saccharine words of “have hope” or “get over it” but in the visceral, raw ways abuse manifests itself in a body.

In this way, Mrs. Dalloway is a deceptive novel, especially on a second or third reading because what we expect the novel to be in fact turns out to be much more than a feminine version of Joyce’s Ulysses. When I first read the novel I read it as a discourse on mind, not paying attention at all to body. It was only on a second reading that I saw body peeking out from hidden corners and I wondered if there was something to the claim that this book is more about abused bodies than just about a troubled woman organizing a party. Then reading about Woolf’s own sexual abuse as a child informed my reading again of Mrs. Dalloway and I noticed the voice of not only body, but a body abused and fragmented. The sentence in the novel that struck me as filled with images of an abused person is the sentence I quote at the top of this article: Clarissa stopping to look at a Dutch picture. The other image is the pervasive trembling of body that courses through the entire novel. From the explosion, the Dutch picture, the aeroplane coursing through the sky, the monsters and spasms that haunt Clarissa and Septimus alike. This led me to a deeper reading of Septimus, a character unthought of in the novel by readers despite his really important presence, as a figure very much akin to Clarissa and also in contraposition to her. After linking these images in my head, the novel stuck out for me as the image of body, sneaking behind the text, trying to get an upper hand on mind that I had been unconsciously looking for in the text. The novel is so richly woven and so well planned out that that first reading skips over the subtler images in the text. This is not a univocal novel with one story to tell; it is multifaceted and rich in texture and depth. The tension in the text between body and mind is rich and multi-layered in ways that this small essay cannot completely mine fully, but even this small examination could show that Virginia Woolf is definitely not a simple walk in the park. She is a fierce thinker whom I think displays passionately and compassionately the pain and loss of humanity, not just for those who have suffered from sexual abuse or any kind of physical or mental abuse, but for all of us who are looking for an articulation of the pain we feel in our bodies, like Mrs. Dalloway, “buying the flowers herself” or Septimus, finding the courage not to be afraid anymore.

[1] Interestingly, DeSalvo, on page one, asserts that Woolf was a sexually abused child and an incest survivor. She then proceeds to give her two intentions for writing the book: first, to use Woolf’s work to form a portrait of the world of the child and adolescent as she understood it. Second, to form a portrait of how Woolf perceived and described herself and her experiences as a child and adolescent by using both works that she wrote during these time periods, and works that she wrote in her maturity describing them (xiii).

[2] These sketches can be found in the book Moments of Being, a collection of Woolf’s autobiographical writings. “A Sketch of the Past,” “Old Bloomsbury,” and “22 Hyde Park Gate” all contain primary source concerning Woolf abused by her half-brothers. Other sources that can be consulted are a letter that she wrote to Ethyl Smith and a letter she wrote to Janet Case.

[3] George was fourteen years older and Gerald was twelve years older than Virginia.

[4] In James King’s biography, Virginia Woolf, he places the aforementioned photographs of Woolf alongside one another.

[5] Diana L. Swanson has an article in this book: Creating Safe Space: Women and Violence. “hence Woolf developed writing strategies of coding, self-censorship, and splitting of event and affect (pg. 85).

[6] These children appear on the page for a moment—as the baby in the carriage of the nanny who sits next to Peter Walsh in Mrs. Dalloway, as the children that Daisy, Peter Walsh’s lover, will lose if she divorces.

[7] In Mrs. Dalloway there are many romps into the mind of another person: Clarissa Dalloway, Septimus Smith, Lucrezia Smith, Mrs. Dempster, Mr. Bentley, Peter Walsh, Richard Dalloway, among others.

[8] It should also be mentioned that sexual abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder carry with them similar symptomatic behavior of abuse. For example, persons suffering from both sexual abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder often have a visceral reaction to touch and acute sounds.

[9] See Judith Butler’s book Gender Trouble for a fuller understanding how an outline is traced upon the body by performance and repetition, especially by society. Our identity as gendered people, even our biological sex, according to Butler, has been traced upon our bodies.

[10] The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard has a detailed section about how wishing to want a body not your own is one of the root causes of despair.

[11] As is common in Woolf, death happens suddenly. There is no prelude to Septimus’s death. He undramatically jumps from the railing.

Bass, Ellen, and Laura Davis. The Courage to Heal: A Guide to Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. New York: Harper, 1988. This book serves as a general reference for women; it is a good text to use to debunk common misconceptions about abuse and women.

Bell, Quentin. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. 2 vols. in 1. New York: Harcourt, 1972. The official biography by Woolf’s nephew can’t be left out in a works cited page because it is the biography that started all the other biographies on Woolf. It does mention her childhood sexual abuse but not with the vigor of DeSalvo—he mentions it, but correlates it to her same-sex attraction for women.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble.

Colman, Andrew, editor. Companion Encyclopedia of Psychology. Volume 2. John Wiley and Sons. 2004. This resource gives clinical definitions of psychological terms and explanation of theory and application; helpful in gleaning data about body image and women.

DeSalvo, Louise A. Virginia Woolf, The Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse On Her Life and Work. Beacon Press, c1989. According to the author, Woolf was a sexually abused child and an incest survivor that deeply impacted her life and work.

Ender, Evelyne. “Speculating Carnality, Some Reflections on the Modernist Body.” Yale Journal of Criticism. 1999. 12.1. 113-130. This article convinced me that I could write a paper connecting Woolf’s sexual abuse to her conception of a fractured body in space because Ender here does a similar thing with illness and the modern conception of body in Woolf and Proust.

Gordon, Mary. “Bodies of Knowledge” in The Mrs. Dalloway Reader. Harcourt. 2003. 97 - 100. This very short article is included in the Mrs. Dalloway Reader. It is a helpful interpretation of the Waves as a brilliant first-person narrative in league with Notes from Underground and Remembrance of Things Past.

Hilsenroth, Mark J. and Segal, Daniel L. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Volume 2: Personality Assessment. “Detection of Child Sexual Abuse.” John Wiley and Sons. (2003?) 459-461. Gives background on various methods and analysis of psychological testing and evaluation, i.e., how does one conclude that a child has been sexually abused?

Hussey, Mark. Virginia Woolf A to Z: A Comprehensive Reference for Students, Teachers, and Common Readers to Her Life, Work and Critical Reception. Facts on File. 1995. This book is very handy for quick Woolf facts that one needs on the fly.

Johnson, Manly. Virginia Woolf. Frederick Ungar Publishing. 1973. Published a year after Bell’s biography, this book is a very short introduction to Woolf’s life and some criticism on her work that was helpful as a contrast to later biographies.

Pipher, Mary, Ph.D. Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls. Ballantine Books. 1994. Popular book that addresses problems facing young adolescent girls today and what adults can do to help girls survive in a male oriented society. These kinds of books have been popular recently; even spawning boy counterparts like Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Lives of Boys.

Swanson, Diana. "Safe Space or Danger Zone?: Incest and the Paradox of Writing in Woolf's Life." in Creating Safe Space: Violence and Women’s Writing. Ed. Tomoko Kuribayashi and Julie Tharp. Albany: State U of New York P, 1997. 79–99. Writes about how when victims of sexual abuse speak “out” about their experiences it may at times have oppressive rather than liberatory consequences.

Ward Jouve, Nicole. "Virginia Woolf and Psychoanalysis" in The Cambridge companion to Virginia Woolf edited by Sue Roe and Susan Sellers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. 246-252. This is an extract from pages in The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf that provided a psychological reading, especially, of Woolf’s own biographical work.

Woolf, Virginia. Moments of Being: unpublished autobiographical writings, 1882-1941. Provides invaluable insight into Woolf’s conception of her own body as she herself viewed it from different stages in her career.

----------------------. Edited by Francine Prose. Mrs. Dalloway Reader. Harcourt. 2003. This critical edition not only provides the complete text of the novel but also includes invaluable selections from her journals, letters and early prose works like Mrs. Dalloway’s Party and a delicious map of Mrs. Dalloway’s walk. The article by Mary Gordon (see cit.) was very helpful in my paper’s evolution.

----------------------. To the Lighthouse. Harcourt Brace. 1955. Probably Woolf’s most taught book in schools, it is a family drama on a rocky beach in Scotland divided into three parts. In this essay, I focus on James and his relationship to his father and how his father disavows his wishes to go see the Lighthouse.

----------------------. Orlando. Harcourt Brace. Woolf’s most playful piece on the body in space; the body in this novel metamorphoses from man to woman—Orlando is not ashamed of her body, not afraid of standing in front of the mirror in awe.

----------------------. The Waves. Harcourt Brace. Considered one of Woolf’s most difficult books, it is probably the chef d’oeuvre of her life’s work, especially the portrayal it gives of abuse; the novel is the disembodied voice of six narrators replete with metaphysical images of the sea and waves.

Young, Barbara. "Virginia Woolf: Her Cries of Joy and Longing” The Yale Journal for Humanities and Medicine. http://info.med.yale.edu/intmed/hummed/yjhm/archives/byoung1.htm. This online article is fairly accessible and easy to read psychological account of Woolf’s life.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

15.9.10

Book Review: Repulsion as Metaphor in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Met Go

|

| Never Let Me Go |

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

11.8.10

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man

It is a cave of light, for he has strung the walls and floor with bright filament light bulbs. It is an act of passive aggression, though. It is his punch in the face to the outside, hegemonic white order. The protagonist imagines the above landlords wondering how so much electricity is being expended. And while the light is being sucked from Monopolated Power and Light, our hero listens to Louis Armstrong and rhapsodies into a metaphysical reverie to match the best of philosophical discourses.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

23.5.10

Quote of the Day for a Viper

She became a perfect Bohemian ere long, herding with people whom it would make your hair stand on end to meet.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

12.3.08

Book Review: The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald

For example, the image of a train track, with a copse of trees in the background is coupled with “In January 1984 news reached me … that on the evening of the 30th of December … Paul Beryter, who had been my teacher at primary school, had put an end to his life” (27). Floating above the narrative voice stands the image of a train track, taken at ground level as if the photographer were lying on his stomach on top of the rails. The track curves a little to the right and vanishes out of view where the school teacher, apparently, “had lain himself down in front of a train” (27). The “photographer” is the character, a stolen shot, of his own death. Looking at the image, the punctum is the shot of the skewed line punctuated with the narrator’s voice. The meaning of the passage is inextricably linked with the image itself. Removed from the pastiche of story, the image is not a referent to the story; it could be inserted into any other narrative of train tracks in the woods, and take on another meaning, altogether.

But, here, as if purposely placed to evoke expression, like the drawing of Beyaert’s classroom (33) coupled with the expression in the text of recognition of another classmate who schooled with the narrator under Bereyter’s instruction. The two, “immediately recognized each other,” both separately reading in the British Museum, coincidentally looking up and noticing one another “despite the quarter-century that had passed” (33). The drawing of the classroom seating plan somehow is supposed to evoke the chance meeting of the two students, and their discussion of their dead professor.

The plan of the classroom, assigned by Bereyter as a classroom assignment, apparently an exercise in drawing space to scale, becomes a memento of both the student’s meeting together by chance in the British Museum, and also, an object representing their shared time in the same classroom in 1946. The images are not seemingly “pictures” of the past. They are rather representations. For example, the photographs of the school children seem to be archival, meaning that they are not autobiographical. The narrator says, about the pictures, apart from his own shared experiences (not pictured) that he was “scarcely distinguishable from those pictured here, a class that included myself” (47). But, you are not supposed to point him out. Nor is the stern teacher in the background supposed to be Beyert. It is as if the history is lost but the images remain.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

24.4.07

Response to Ngugi wa Thiong’o speech at Southeastern Louisiana University

A new book by Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Wizard of the Crow, satirizes the West from an African perspective; Like Achebe, he brings old questions to the fore about Western colonialism and Christianity.

The halls of Southeastern's Vonnie Borden theater was filled to hear the world's foremost East African writer. Having just completed a novel about a fictional despotic African leader, Ngugi also spearheads a program at Irvine, The International Center for Writing and Translation, to create and distribute indigenous African tongues apart from Western translations.

Whether or not the Colonial experiment in Africa tainted Christian missionary activity or whether Christian missionary activity is itself tainted is probably not the right approach to tackle Western Christianity’s attempt to proselytize non-Western peoples. It is not that the missionary activity is inherently tainted, but rather that the approach was marred, most significantly because of the imperial and univocal nature of Colonialism — the structure of Colonialism did not allow for, what we would call today, the recognition of the language of the subaltern. The Christian missionary movement was lead by many good-intentioned Christians. But, what many Christian missionaries failed to realize is that they were not only teaching Christian doctrine in their own Mother tongues, not the language of the people, but they assumed that the conquering language had a stake in knowledge that was not apparent in the indigenous languages. Although some missionaries attempted to learn the language of the conquered African colonies, for the most part, the idea of Colonialism was to teach them the history of the Conqueror, the language of the Conqueror, and the beliefs of the Conqueror. Get a few educated elites to learn English, for example, and to translate the ideologies and beliefs of the people into English. In this paradigm, there is no attempt to raise the native languages to the status of the elite — as if Jesus spoke English! Jesus did not speak English, as Ngugi playfully reminded us last week; Jesus spoke a rural form of Aramaic and spoke in simple terms using the imagery and language of the people he taught and lived among in Galilee, which is why it is sometimes very difficult to understand his parables and sayings. But his sayings were translated into the language of the educated elite, which is Greek in this case, and this is how the message of the New Testament writings was originally communicated. But perhaps the Jesus of Colonialism did not learn anything after 2000 years old and is still up to his old tricks, so the language of the elite is still the language of the Conqueror, in this case, English or French, or Dutch, or whatever the language of the conquering nation happens to be. But take this language and try to translate native Swahili to mirror it is obviously going to have problems. But of course, the Harvard educated professor cannot be told by a graduate from the University of Treetops that he speaks good English. “Of course I speak English. I went to Harvard!” Ngugi here is parodying how language is classed, like race or ethnicity. How can the Mother tongue of the Western Nations describe a God (or Gods) to a community of peoples who have their own language of God (or Gods)? It just doesn’t make sense. This has been parodied, as in the short story, "The Gospel According to Mark" when an unbeliever, Espinoza is crucified on a tree like Christ — the people believed him to be the Savior. But this view is terribly pejorative and simplistic. It is as if to say, people of a non-Western ideology or bound to mistake Western religion to the point of sheer, nonsensical violence. This does not make sense. Nor does the univocal injunction to impose one language, one faith, one way of thinking on a collection of people that do not fit into the hegemonic whole. Ngugi seems to be saying that Globalization is partly to blame for this branding of language and culture that seems to disavow the minority of a language for the sake of its own language, not needing to be mediated by a language like English or French to be understood or disseminated. But you may say, there is something innate about all human beings that no language, no matter how univocal its insistence to be the language of choice, can override the dignity and value of humanity, because any knowledge that is worth having is knowledge of a humanity that is universal. But the problem with this kind of thinking is that it ignores the nuances of languages and the inability to express in subtle language — say the texture of snow or the agronomy of the Kenyan plains — that cannot be translated. True, maybe translation from Nilotic to English actually enhances the Nilotic language — but for who? who benefits? Not the Nilotic speaker, but the English one. So, it seems this is what Ngugi is trying to do; he is not trying to disparage English or any other language, but simply insisting that the indigenous languages of a people, to be of value, to provide knowledge for its people, has to be kept within its own language families. Ngugi would say that a novel written in Swahili needs to be translated from Swahili to Nilotic as it is, not mediated by English or French. It would be like translating a letter written in English into another language and then using that language, not English, to translate it into another language. The more permutations of language the more diluted and lost the original becomes. I can see how this can become very problematic and detrimental the more it perpetuates itself. Although I, and millions of other people, know only Western Romance languages and have only read non-Western texts translated into Western languages, it still does not preclude the fact that my language, my Western Romantic language does not need to ipso facto the one language that swallows up the rest.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

15.3.07

Book Review: "The Farming of Bones"

|

| Edwidge Danticat's novel Farming of Bones |

The novel is a study in trauma: using sensuous language Danticat writes the body in pain. Like a patient in therapy, when the story is retold, the subsequent retellings of the story, four things happen.

- The body remembers. This is why Amabelle says, “This past is more like flesh than air; our stories testimonials …” (281).

- The story, as a testimonial, repeated and retold differently and with divergent perspectives, with an occasional interpretation by the therapist is revisited.

- The third consequence of this telling is a recognition that the story is held in tension with the official story — here the story told by the Dominican victors against that which is held in the heart of survivors or lost forever with the dead.

- The language acts as a kind of counter-narrative to the anger and hatred against the black, coffee-colored, bodies of the Haitians.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

5.12.06

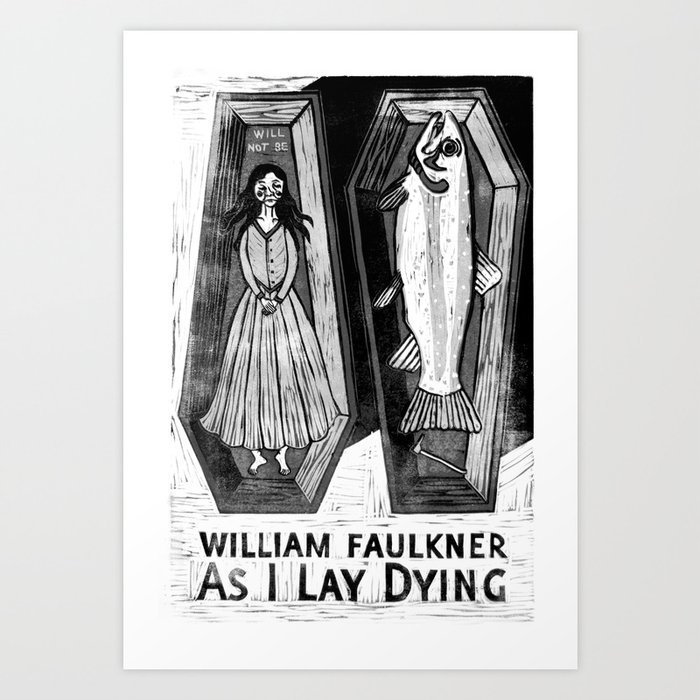

Book Review: Warmish-Cool Pleasure in As I Lay Dying

William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypal quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon.

William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypal quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon.William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, is the archetypical quest story, one of the most satisfying and basic plots in the literary canon. Like Homer’s The Odyssey

This pleasure is what makes one reader say, “this book is so funny” and another reader to say, “this book is so sick!” There is a voyeurism ingrained in the reader to want to find out more about this strange, poor family and what compels them to undertake their journey no matter how much you feel or think their journey is depraved. The reader is interested in as many details as can be garnered that can aid in putting the narrative pieces together to understand the journey arc of the novel. This is highly pleasurable. Added to this is the structure of the novel itself. It is told by a series of monologues written in a stream of consciousness style. The reader puts together the pieces of the Bundren’s journey through the varied and limited mental states of the characters. Being inside of the mind of a character provides pleasure, for it is a romp within the mental imagery of another “person”.

What enhances the pleasure for the reader in this scene is how Faulkner situates the text within the narrative structure of the chapter. We are inside Darl’s troubled head here. But we hear his father ask him, “Where’s Jewel?” (8). It is in the interstices of this question that Darl fantasizes about going to the water-filled gourd at night, stirred awake, to see the stars in the water inside the gourd, to be intoxicated into an erotic reverie. But the text reverts back to reality. Back to the scene where his father had asked him about Jewel’s whereabouts. The text brings us in and out of internal journeys into external journeys and out again and back again. This is what gives the novel a heightened sense of journey for the reader. The pleasure of the text is not only Darl’s own bodily pleasure, but the text itself becomes an erogenous zone. The text is a sensuous locus of pleasure as well as the pleasure of the character Darl himself, despite Darl’s own descent into madness.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

8.5.06

Book Review: Body, Pain, Torture and the Cogito - Unmaking and Making of the World in Anil’s Ghost

The body is constantly barraged with images, perceived by the image, informed by the image, speaks through the image and the text; the body has knowledge that language cannot express. The fallacy of torture is that it seeks from the body knowledge that the body cannot give. In an image-saturated society, the problem of the cogito, both the Cartesian indubitable certainty of mind and the split between mind and body fostered by the Enlightenment and onwards, has erroneously bifurcated the body and the mind, has wedged the two apart by scientific discourse; the mind has become privileged thus being subsumed under the subtitle of peripheral concern. The body, therefore, has become unnoticed, not a substantial claim to certainty, not given a voice in the political realm and not perceived holistically as an agent of viable literary discourse. Nietzsche and Schopenhauer understood this dynamic of pain needing a way to express itself; Nietzsche, forever the romantic, embraces pains because it gives him knowledge, it does not confine him to an unalive corner, but rather, pain, is an expression of life and living dangerously.

So in an effort to give the body back to poetry, the body, corporeal and enfleshed is a text and the contemporary novel is a place of transformation where this body can speak above the technological, 21st-century din and the political discourse that govern legislation, human rights action, and world-systems. The body haunts the text in which the cogito, the voice of reason, the privileged discourse of reason holds sway; because of this privileging of mind, “the body in pain” is unmade by the cogito – not into a real, tortured person, but rather a body politic, a set of nations pinned against one another on the global stage, a specter.

An ethical response that is genuine is lost by the cogito because of its insistence to bifurcate and divide, giving literary discourse an emphasis on mind instead of the body.

An agency of language for the body is uncertain in a tyranny of the cogito. “The body in pain” is subsumed by the cogito, the logical slice of reason; it is easier to think about the conflicts of nations instead of the real human beings involved in suffering, torture, and war, thus a feeling emerges that says there is no need for an ethical response to the real suffering of the other.

Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje is an example of the novel being able to give a voice to the pain in the body, speaking in the corners of literary texts, where a single line is enough to expose “the body in pain,” the body mutilated, the body abused (Scarry 11). Ondaatje’s novel is about torture and political violence set in the contemporary sphere of globalization that assumes different approaches to “the body in pain”. Elaine Scarry writes, “Physical pain does not merely resist language but actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is heard” (4). The voice of the tortured body, the mutilated body is destroyed by pain, reverted back to a state a priori to language; this is cause for ethical response, a giving back of a voice, The body interrogated, mutilated, evaporated is silenced, made obliterated of content (Scarry 33). The body in pain loses its voice in these novels giving rise to an ethical call to action not written by the cogito which either makes or unmakes the world via a two-pronged model: a creation of the world with Gamini Diaysena, an emergency room doctor and Ananda Udugama, an artist who reconstructs the face of the dead, or an unmaking of the world with the cold, slicing knife of Western reason symbolized by Anil Tissera, a UN forensic anthropologist.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

10.11.05

Book Review: The Hours

It’s funny the images that Cunningham frequently uses in his novels. In an interview with Cunningham in the Kenyon Review (I think it’s the Kenyon Review), he talks candidly about his books and how they have been received by the general reading public; especially his role as a gay author writing books that do not necessarily fit into the Gay and Lesbian genres. It could be said that Cunningham is breaking new ground by writing books from a queer perspective accessible to the non-queer type and not solely formula fiction. Typical gay books tend to follow a formulaic outline: 1.) boy (or girl) is unsure of his/her sexuality 2.) has a sexual experience 3.) there is talk about the danger of AIDS 4.) then “coming out” to family and friends 5.) maybe more sex 6.) falling out with partner 7.) and either a reconciliation or more commonly, going separate ways. I have even heard that some formula fiction (whichever the genre) is so predictable that you can flip through the book quite easily and find all the parts. While not all queer fiction is formulaic, the books I’m talking about are either “coming out” books, gay bildungsromans with stereotypical characters, or they tend to be Harlequin romances or Barbara Cartland yarns with a homoerotic theme. Suffice it to say, hopefully, Cunningham's books represent a shift in queer fiction. He doesn’t even use the word “gay” (if at all) in his novels. Sexuality is fluid for him; what I mean is that sexual identity is not fixed in stone; like the Kinsey model -- none of us are either completely one way or the other; most of us lie somewhere in the middle of the sexual spectrum.

And also, as we mentioned in class — we read novels because we want to read them; we shouldn’t read a novel because a character has or has not a particular “orientation” — so what if a character is gay, straight, transgendered, bisexual or whatever? It’s the same problem we affix to other genres — Christian fiction, historical fiction; as if the genres themselves dictate how we are supposed to enjoy the book. Someone mentioned in class last night that walking into a Barnes & Noble, you get the sense that the books are choosing you not you choosing them.

I can’t help but mention the fact that in the interview in the Kenyon Review the interviewer mentions that in every one of Cunningham's novels there is mention of baking a cake. In Flesh and Blood the mother is baking a cake for a birthday party; in The Hours, Laura Brown sticks her hands into cake dough, evanescent of her repressed sexuality and in a Home at the End of the World, Bobby learns to bake a cake from his best friend’s mother and eventually becomes a chef. Responding to this observation about cakes in his novels, Cunningham laughed and said that it wasn’t done on purpose. But, he said, it was true — cakes are everywhere in his works. If you want to know the symbolism of something in a book don’t ask the writer because he will deny any kind of signification; writers don’t like to give away “why” they wrote a book (as if there is something to “give away”);. Readers, however, are different from the writer of the book in that we want to discover meaning behind recurring images in a novel but authors are reluctant to say, “yes I meant this when I wrote that.” If I were to give meaning to baking in Cunningham I would say that he is very much involved with domesticity, uncovering the mundane “stuff” we do in our everyday superficial lives. But, he just as well may say that it was a coincidence.

Speaking of cakes and domesticity, it is interesting to note how Cunningham “places” his novels. He doesn’t portray starving people in Ethiopia nor does he showcase the horrors of war in Iraq — his novels are about sometimes superficial peoples’ lives in an artificial world trying to find a home. Clarissa in the Hours lives in a fabulous apartment; she is privileged; she is throwing a party for her former lover; like Mrs. Dalloway, it’s all rather superficial. What’s the point? What’s the so what? Cunningham is writing from what he knows just as Woolf wrote from what she knew, her (and his) collection of memories and experiences that serve as the fodder for the novels. What’s more universal: dying of AIDS in Uganda or dying of AIDS on the Upper West Side?

I don’t know if the Hours (or any of Cunningham’s novels) will make the list in the years to come. It’ll be interesting to see what’s included in the canon before my own life is finished. The Hours is a fine book; it is not an imitation of a previous masterstroke, but nor is it a genius piece of work either. I enjoyed it a second time after reading so much Woolf in a short span of time. It was a nice dessert! I can’t help but think, though, that perhaps cake may be Cunningham’s only perduring legacy.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

11.10.05

Journal Entry on Orlando by Virginia Woolf

Nature and letters seem to have a natural antipathy; bring them together and they tear each other to pieces.

- Virginia Woolf

In reading the biography of Orlando, I have to step back and wonder what sign indicates who we really are. I usually have taken signs for granted, a given — signposts to help guide me in this strange land (1). Take de Saussure’s tree, for example. The sign for tree seems easy enough, but the sign for “me” is more difficult to get a hold of, despite the omnipresence of our bodies — we can’t escape ourselves, yet we remain indefinitely perplexed by our very selves (2). Especially if we have been disrupted somewhere along the way. Abuse. Violence. These traumas can either be signs of grace or asphyxiation. The signs no longer work. Or grace seeps in and we can see again. The signs that clue us into our gender are based on assumptions about what it means (how it is comprehensible) to own a phallus between your legs or a pair of scissors on your lap (tongue in cheek). These assumptions either become whole or fractured.

Gender is not only a lesson in anatomy – yes, certain physical features of our anatomy, so we are told, designate us as male or female — but there are other dynamics at play here. Either you are a male or a female? It seems easy enough, but already, before the child even leaves the mother’s womb, the infant is beset with the problem of sex and gender. Gender presents a host of possibilities, many of them rife with problems. Just think of all the restrictions that gender places on us (that Orlando seems to be liberated from, miraculously enough).

If you have a penis you cannot speak of shopping with the same reckless abandon as you would if you have a vagina. The who-has-what is culturally conditioned. Orlando can play (and did) both gender sides. Case study: A boy playfully applies his mother’s lipstick when no one is looking (see the film, Billy Elliot or L.I.E.) or a girl dodges her father’s resistance and joins the boxing league, despite the opposition. A father tentatively embraces his son after his ex-wife drops him off. Why is it that these gender roles are so fixed in culture? I know the question is hopeless, but I ask it indefatigably.

Gender remains a cultural construct, while sex is a hazy reminder of our once intimate link with nature. Now that we have shaken off nature, any idea of a utopian society in the feigned vein of a Rousseau (or even Plato) have fallen by the wayside. We are products of culture, and thus, depending on our cultural milieu, must endure certain gender roles that society places on us. I guess we could fight it but I am not going to risk the humiliation of wearing a dress to class with burgundy lipstick. Maybe Orlando can wake up one day, a different gender and amiably stride into her new role – but, I must confess, I don’t think I could do that. The gender roles are too much ingrained in me. Yeah, some gender constructs I can elide easily enough — like the idea of blue and pink as being exclusively male or female -- so that they no longer serve as signs of gender, but rather remain as spectrums in the rainbow of light No matter what we do to fight it, I feel, the legacy of the west remains, placing ideas in opposition (form and matter, good and evil, black and white) as if the tension between the two will actually produce something that is knowledgeable and meaningful. We are so binary about the whole thing. I hate that.

As a boy, I am sure (because Lacan assures me (3)), I looked in a mirror and saw an image reflecting back that I assumed was a whole image of me, even though it was a misrecognized image, incomplete, a partial imago of the real me, flabby, infantile and totally dependent on mum and pop. And I am sure, completely self-involved — more than I am now! Somewhere along the way, I looked in the mirror, butt-naked — like Orlando — and was gendered. Not solely by me. But by my parents. TV. Et Cetera. I was male. I am a male. I was wondering? Especially after a few beers. Will I wake up one day and find myself changed? Orlando had no qualms about her sex: there was no doubt about his sex (pg 1) but she is two-gendered in the novel. It makes for awkward pronoun usage because you don’t know if you should use masculine or feminine pronouns to describe her. In the novel, it is not problematic at all because the narrative is progressive. Woolf brilliantly avoids any grammatical ambiguity although the text remains rather ambiguous. Or is it androgynous?

Here comes Dick, he's wearing a skirt

Here comes Jane you know she's sportin' a chain

Same hair, a revolution

Same build, evolution

Tomorrow who's gonna fuss?

And they love each other so, androgynous

Closer than you know, love each other so, androgynous

We'll don't get him wrong, and don't get him mad

He might be a father but he sure aint a dad

And she don't need the advice that is sent to her

She's happy the way she looks, she's happy with her gender

And they love each other so, androgynous

Closer than you know, love each other so, androgynous

Mirror image, see no damage, see no evil at all

Cupie dolls and urine stalls will be laughed at

The way you're laughed at now

Something meets boy and something meets girl

They both look the same they're overjoyed in this world

Same hair revolution

Unisex evolution

Tomorrow who's gonna fuss?

And tomorrow Dick is wearing pants,

Tomorrow Jane is wearing a dress

Future outcasts and they don't last

And today people dress the way that they please

The way they tried to do in the last centuries

And they love each other so, androgynous

Closer than you know, love each other so, androgynous.

PDF Copy for Printing________________

(1) I stole this from the title of Walker Percy’s posthumous collection of essays Signposts in a Strange Land.

(2) Percy wrote about that too in his book, Lost in the Cosmos. He describes two phenomena that I can remember: walking by a mirror in a department store and not knowing who that person was you just walked past, so you back up and see and startled to discover it was your reflection in the mirror. Or why is it that when you look at a photo, for instance, a family portrait, the first person you seek out is yourself?

(3) See Lacan's writings on the subject in “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience”

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.

I am an educator and a writer. I was born in Louisiana and I now live in the Big Apple. My heart beats to the rhythm of "Ain't No Place to Pee on Mardi Gras Day". My style is of the hot sauce variety. I love philosophy sprinkles and a hot cup of café au lait.