|

| Jacques Lacan, French Psychoanalyst, and Theorist |

According to Jacques Lacan (2006), “the subject’s unconscious is the Other’s discourse” (p. 16). Lacan’s correlative thesis is “the unconscious is structured like a language” (1998, p.2).

Lacan sees in Edgar Poe’s short story “The Purloined Letter” (1844) a privileged illustration of the Other’s discourse in relation to the unconscious and the structure of a letter to always contain the possibility of return. In the Poe detective story the interrelationship between the primary characters: the Queen, the King, the Minister D., and Dupin (a French version of Sherlock Holmes) are each in turn inhabited by a letter and its undisclosed contents, seen first as a compromising piece of evidence against the Queen, and then, as becomes evident in Lacan’s reading, a metaphor for the function of the Other modulated by the presence and absence of the letter and the way in which the Other, which does not “exist,” inhabits and is inhabited by the subject. The plot of the Poe story is thus: the compromising letter is displayed in full sight when the King enters the royal boudoir, “the primal scene.” Hoping to avert the King’s eye from the incriminating letter, the Queen places the letter face down so as not to attract undue notice. The Minister D., at that moment, walks in and is able to discern the Queen’s deception because of his “lynx eye.” Producing an identical looking letter from his breast pocket, the Minister concocts a discourse with the King while at the same time nonchalantly placing the facsimile letter on the bureau. The Queen can do nothing. When the conversation between Minister D. and the King is terminated, the Minister picks up the Queen’s letter and leaves the room. The Queen is dispossessed of the letter by the crafty Minister. By possessing the letter, the Minister is in hold of power over the Queen. The Queen promises a sum of money to the person who can retrieve the letter and return it to her. The detective Dupin orchestrates a plot to retrieve the letter from Minister D. Once he determines the location of the letter -- between the jambs of the fireplace -- he craftily replaces it with a facsimile and is able to restore the letter to its proper place and reap a reward.

Lacan sees in Edgar Poe’s short story “The Purloined Letter” (1844) a privileged illustration of the Other’s discourse in relation to the unconscious and the structure of a letter to always contain the possibility of return. In the Poe detective story the interrelationship between the primary characters: the Queen, the King, the Minister D., and Dupin (a French version of Sherlock Holmes) are each in turn inhabited by a letter and its undisclosed contents, seen first as a compromising piece of evidence against the Queen, and then, as becomes evident in Lacan’s reading, a metaphor for the function of the Other modulated by the presence and absence of the letter and the way in which the Other, which does not “exist,” inhabits and is inhabited by the subject. The plot of the Poe story is thus: the compromising letter is displayed in full sight when the King enters the royal boudoir, “the primal scene.” Hoping to avert the King’s eye from the incriminating letter, the Queen places the letter face down so as not to attract undue notice. The Minister D., at that moment, walks in and is able to discern the Queen’s deception because of his “lynx eye.” Producing an identical looking letter from his breast pocket, the Minister concocts a discourse with the King while at the same time nonchalantly placing the facsimile letter on the bureau. The Queen can do nothing. When the conversation between Minister D. and the King is terminated, the Minister picks up the Queen’s letter and leaves the room. The Queen is dispossessed of the letter by the crafty Minister. By possessing the letter, the Minister is in hold of power over the Queen. The Queen promises a sum of money to the person who can retrieve the letter and return it to her. The detective Dupin orchestrates a plot to retrieve the letter from Minister D. Once he determines the location of the letter -- between the jambs of the fireplace -- he craftily replaces it with a facsimile and is able to restore the letter to its proper place and reap a reward.

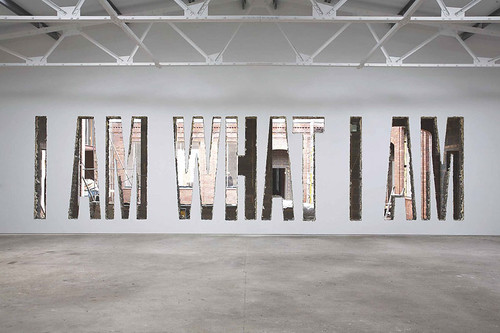

The Other functions in what Lacan terms the symbolic order. Lacan’s “Seminar on the Purloined Letter” is part of his larger reading of Freud's Beyond the Pleasure Principle. In this book Freud speculates on the existence of an inextricably charged compulsion in each human being to repeat past, original trauma (Widerholungszwang). Lacan claims repetition compulsion is to be understood as a structure of repetition based on the insistence of something like a letter in a long signifying chain. The letter is a material signifier in the Poe story. According to Lacan’s developmental model of human subjectivity articulated in his “Mirror Stage” essay (1942), the self, upon leaving dyadic union with the Mother is captured into a “symbolic dimension” which hitherto “binds and orients” it (Lacan 28). Schooled in the thought of Alexander Kojève’s reading of Hegel, Lacan’s theory of intersubjectivity is based upon a theory of alterity that is spelled out by the equation “the I is the Other.” Rimbaud, the boy poet, put it nicely, "Je est autre." In other words, there is no subjectivity without intersubjectivity. I cannot name myself as an “I” in the symbolic order without an embedded relationship to something outside myself which defines me. The birth of the subject arises out of an imaginary misrecognition which in turn is sublimated under the domain of the symbolic order, so that it is “the symbolic order which is constitutive for the subject” (Lacan 29).

The subject is divided between a mirror image of its self, what Lacan calls the imaginary, the topos of images, dreams, and libidinal desires, and the symbolic order, the purview of language, the law, thought, and desire for an Other. The subject is thus barred from access to a signified, written out in the formula S/s, and is circumscribed under the auspices of the signifier. The realm of the imaginary is related to the symbolic but there is a bar wedged between the gestalt of the spectral image and the name of the father, the law, of the symbolic order. What constitutes the self is an intractable search to locate the lost wholeness of the Other. In this way, Lacan rewrites Freud’s observation that the little child realizes his mother (the m/Other) does not have the phallus. Upon realizing that the mother does not, in fact, have the phallus, the child cognizes that the phallus must be lost and goes in search of it in order to restore it to its proper place. We have here the Lacanian explanation of symbolic desire built upon Freud’s idea of the Oedipal Complex as well as the repetition compulsion. The search for the mother’s phallus is forbidden by the Father/Law. The law intrudes in the form of the symbolic father who cuts a decisive “no” into the child’s forbidden desire.

References

Lacan, J., & Fink, B. (2006). Ecrits: The first complete edition

in English. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

----, & Sheridan, A. (1998). The four fundamental concepts of

psychoanalysis: the seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XI. New

York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Muller, J. P., & Richardson, W. J. (1988). The Purloined Poe: Lacan,

Derrida & psychoanalytic reading. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

in English. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

----, & Sheridan, A. (1998). The four fundamental concepts of

psychoanalysis: the seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XI. New

York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Muller, J. P., & Richardson, W. J. (1988). The Purloined Poe: Lacan,

Derrida & psychoanalytic reading. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.